Colorectal cancer genetics

Is colorectal cancer a hereditary cancer?

Only about 5 percent of colorectal cancers are inherited. But if someone in your family has colorectal cancer because of an inherited gene mutation, particularly a parent or sibling, you have a higher chance of being diagnosed with the cancer, too.

The first clue that colorectal cancer could be inherited is when someone younger, under the age of 50, is diagnosed. The next clue is a history of colorectal cancer in that family. Having a parent, sibling or child with the disease increases the lifetime risk from about 5 percent to 15 percent. If a relative with cancer is younger than age 50, the risk is even higher. And if there’s more than one first-degree relative with colon or rectal cancer, the risk rises even more.

See “Does colon cancer usually run in families?” on the Cleveland Clinic website.

In most cases of colorectal cancer, the DNA mutations that lead to cancer are acquired during a person’s life rather than having been inherited. Certain risk factors probably play a role in causing these acquired mutations, but so far it’s not known what causes most of them.

There doesn’t seem to be a single genetic pathway to colorectal cancer that’s the same in all cases. In many cases, the first mutation occurs in the APC gene. This leads to an increased growth of colorectal cells because of the loss of this “brake” on cell growth. Further mutations may then occur in other genes, which can lead the cells to grow and spread uncontrollably. Other genes that aren’t known yet are probably involved as well.

See “What Causes Colorectal Cancer?” on the American Cancer Society webpage.

Hereditary genes

The most common inherited syndromes linked with colorectal cancers are Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC) and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), but other rarer syndromes can increase colorectal cancer risk, too.

Lynch syndrome is the most common hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, accounting for about 2 percent to 4 percent of all colorectal cancers. In most cases, this disorder is caused by an inherited defect in either the MLH1, MSH2 or MSH6 gene, but changes in other genes can also cause Lynch syndrome. These genes normally help repair DNA that has been damaged.

The cancers linked to this syndrome tend to develop when people are relatively young. People with Lynch syndrome can have polyps, but they tend to only have a few. The lifetime risk of colorectal cancer in people with this condition may be as high as 50%, but this depends on which gene is affected.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is caused by mutations in the APC gene that a person inherits from parents. About 1 percent of all colorectal cancers are caused by FAP.

In the most common type of FAP, hundreds or thousands of polyps develop in a person’s colon and rectum, often starting at ages 10 to 12 years. Cancer usually develops in one or more of these polyps as early as age 20. By age 40, almost all people with FAP will have colon cancer if their colon hasn’t been removed to prevent it.

Source: “Colorectal Cancer Risk Factors” (American Cancer Society, 2023)

Other genes involved in breast cancer

- ATM

- BARD1

- CDH1

- CHEK2

- NF1

- PALB2

- PTEN

- RAD51C

- RAD51D

- STK11

- TP53

- CHEK2

- PALB2

Disparities in breast cancer genetics?

African American and White Women share same genes that increase the risk of breast cancer

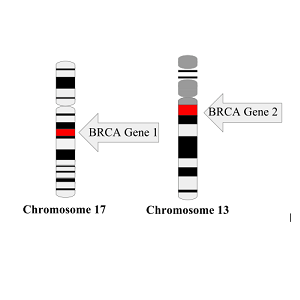

The same genes that increase the risk of breast cancer in U.S. White women also greatly increase breast cancer risk among African American women. Previous studies of women of African ancestry were too small to assess genes other than BRCA1 and BRCA2.

The same genes that increase the risk of breast cancer in U.S. White women also greatly increase breast cancer risk among African American women. Previous studies of women of African ancestry were too small to assess genes other than BRCA1 and BRCA2.

“This means that the multi-gene panels that are currently available to test women diagnosed with breast cancer or women at high risk due to their family history will be useful for African American women,” explains Julie Palmer, ScD, (left) of the Boston University School of Medicine.

Researchers in 2020 sequenced the germline (inherited) DNA from 5,054 African American women with breast cancer and 4,993 age-matched African American women without cancer for mutations in 23 genes linked to a predisposition for cancer. They then estimated the risks of developing breast cancer associated with having a mutation in any of the genes.

- Source: “African American and White Women Share Genes that Increase Breast Cancer Risk” on the Boston University School of Medicine website

- See the full text of the scientific paper “Contribution of Germline Predisposition Gene Mutations to Breast Cancer Risk in African American Women” by Julie R Palmer et al.

Rates of genetic mutations similar between Black and White women diagnosed with breast cancer

In a 2021 study of 3,946 Black women diagnosed with breast cancer and 25,287 White women also diagnosed with the disease, the rates of genetic mutations in genes linked to breast cancer were similar. Among the Black women, 5.65% had a mutation in one of the 12 genes, compared with 5.06% of the White women, a difference that is not statistically different.

In a 2021 study of 3,946 Black women diagnosed with breast cancer and 25,287 White women also diagnosed with the disease, the rates of genetic mutations in genes linked to breast cancer were similar. Among the Black women, 5.65% had a mutation in one of the 12 genes, compared with 5.06% of the White women, a difference that is not statistically different.

The researchers, led by Susan Domchek, MD, (right) of the University of Pennsylvania, concluded that all efforts should be made to ensure equal access to genetic testing to minimize disparities in care and outcomes in women diagnosed with breast cancer.

- Source: “Do Black Women Diagnosed With Breast Cancer Have Higher Rates of Genetic Mutations Than White Women?” by Jamie DePolo on the breastcancer.org website

- See the full text of the scientific paper “Comparison of the Prevalence of Pathogenic Variants in Cancer Susceptibility Genes in Black Women and Non-Hispanic White Women With Breast Cancer in the United States” by Susan M. Domchek et al.

Recent news about disparities in genetic mutations

Breast cancer genetic testing

Get Genetic Counseling Before Testing

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says it’s important to get genetic counseling before genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in order to determine whether you and your family are likely enough to have a mutation that it is worth getting tested. Usually, genetic testing is recommended if you have:

- A strong family health history of breast and ovarian cancer

- A moderate family health history of breast and ovarian cancer and are of Ashkenazi Jewish or Eastern European ancestry

- A personal history of breast cancer and meet certain criteria (related to age of diagnosis, type of cancer, presence of certain other cancers or cancer in both breasts, ancestry, and family health history)

- A personal history of ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer

- A known BRCA1, BRCA2, or other inherited mutation in your family

Carletta (above) tested negative for BRCA mutations after being diagnosed with breast cancer.

Source: “Genetic Testing for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer” (CDC)

How is genetic testing done?

Genetic testing is typically done only if you and your health care team feel that it’s the best thing for you and your family. The first step is to collect information about your personal and family medical history. A genetic counselor or other trained professional will go over this information to help determine:

- Your risk of developing cancer,

- If genetic testing might be helpful for you, and

- If so, what specific gene changes should be tested for

Even if the counselor recommends you be tested, you still have the right to refuse it.

Genetic tests for cancer are typically done on a sample of blood, saliva, or cheek cells from swabbing the inside of your mouth). Once the results are ready (often 2-3 weeks later), your genetic counselor will share the results with you.

For more reasons to seek genetic counseling, see “Genetic testing for people who have been diagnosed with breast cancer” (FORCE: Facing Hereditary Cancer Empowered)

Susan G. Komen says its “My Family Health Portrait” is an internet-based tool that’s easy to access on the web and simple to fill out and should only take about 15 to 20 minutes to build a basic family health history. It assembles your information and makes a “pedigree” family tree that you can download and share with family members or send to your health care practitioner. It is private–it does not keep your information.

Don’t rely on direct-to-consumer genetic testing to determine your BRCA status. More than 1,000 variants of the BRCA genes are known to increase the risk of cancer. 23andMe genetic testing , the only FDA-authorized, Direct-To-Consumer BRCA Test, detects only the three variants most common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. These variants are rarely found in people of other ethnicities, the company cautions.

If you had genetic testing before 2014 that was negative for breast cancer mutations, you might want to consider getting an updated gene test. Genetic tests before 2014 did not include testing for important BRCA mutations, the PALB2 gene and other mutations.

Genetic testing after a breast cancer diagnosis

Genetic testing may be recommended after a diagnosis of breast cancer to look for gene mutations that have been inherited. Some breast cancer treatments are given only to people who have certain inherited gene mutations.

Knowing about inherited mutations and the risk of cancer can also be important information for other family members.

Testing for gene mutations within the tumor itself may also be done. For some people, this can help guide treatment.

More at: Genetic Testing After a Breast Cancer Diagnosis (Susan G. Komen)

Paying for genetic testing

Insurance coverage for genetic counseling and testing

Most health plans cover genetic counseling and testing for inherited gene mutations linked to cancer in people who meet the national guidelines. The cost of testing and your out-of-pocket charges may vary based on several factors. People who are denied coverage for genetic testing can file an appeal (FORCE has sample appeal letters). About half of appeals are approved.

Most health plans cover genetic counseling and testing for inherited gene mutations linked to cancer in people who meet the national guidelines. The cost of testing and your out-of-pocket charges may vary based on several factors. People who are denied coverage for genetic testing can file an appeal (FORCE has sample appeal letters). About half of appeals are approved.

Medicare and Medicaid

Genetic counseling and testing is typically covered by Medicare for people already diagnosed with cancer who are in treatment or for whom test results may affect their care. Most state Medicaid programs cover genetic testing for BRCA and Lynch Syndrome mutations for people who meet requirements, which vary by state. You can read more about Medicare and Medicaid coverage of genetic testing here.

Financial assistance or low cost genetic testing

JScreen is a national program based out of Emory University in Atlanta that provides discounted at-home genetic counseling and testing with financial assistance available. Many laboratories offer low-cost genetic testing or financial assistance programs. Programs vary, so if you are not eligible for assistance through one lab, consider contacting other labs to see if you qualify. For more information, see “Paying for Care” on the FORCE website.

Disparities in breast cancer genetic testing?

Racial Disparities Persist in Genetic Testing

Carlette Burton knew she had a family history of cancer, but she never looked into her genetic risk for BRCA-related cancer until she found a concerning lump in her breast during a self check. After her diagnosis, she had genetic testing done and found out that she has a BRCA mutation.

Burton’s mother also had been diagnosed with breast cancer in her 30s. Her grandmother had had breast cancer, too. She is one of five sisters, “but I don’t ever recall a doctor saying we should get tested.”

Read more at “Racial disparities still persist in genetic testing for BRCA-related breast cancer” by Tracey Romero on the Philly Voice website (April 6, 2021)

Black women less likely to undergo genetic counseling and testing

About five percent of both Black and white women have a genetic mutation that increases their risk of breast cancer, according to a new study of nearly 30,000 patients.

However, compared to White women, Black women are much less likely to undergo genetic counseling and testing, largely due to differences in physician recommendations or access to care.

“Our efforts should focus on ensuring equal access to testing to minimize disparities in care and outcomes,” said researcher Susan Domchek of Penn Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (June 11, 2021)

Read more at “Black and White Women Have Same Mutations Linked to Breast Cancer Risk” on the Penn Medicine website (June 11 , 2021)