Breast cancer genetics

Is breast cancer a hereditary cancer?

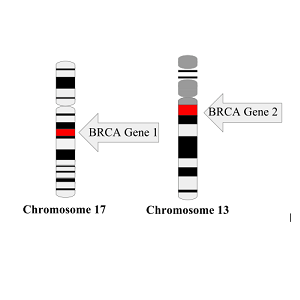

About 5% to 10% of breast cancer cases are thought to be hereditary, meaning that they result directly from gene changes (mutations) passed on from a parent. The most common cause of hereditary breast cancer is an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene.

Other gene mutations can also lead to inherited breast cancers. These gene mutations are much less common, and most of them do not increase the risk of breast cancer as much as the BRCA genes. The most common: ATM, PALB2, TP53, Chek2, PTEN, CDH1, and STK11 genes.

Source: “Inheriting certain gene changes” (American Cancer Society, 2021)

For more information about these gene mutations, see: Inherited Gene Mutations (Susan G. Komen) and Hereditary Breast Cancer (Facing our Risk)

BRCA genes

The most common cause of hereditary breast cancer is an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene. In normal cells, these genes help make proteins that repair damaged DNA. Mutated versions of these genes can lead to abnormal cell growth, which can lead to cancer.

- On average, a woman with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation has up to a 7 in 10 chance of getting breast cancer by age 80.

- Women with one of these mutations are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer at a younger age, as well as to have cancer in both breasts.

- Women with one of these gene changes also have a higher risk of developing ovarian cancer and some other cancers.

- Men who inherit one of these gene changes also have a higher risk of breast and some other cancers.

- In the United States, BRCA mutations are more common in Jewish people of Ashkenazi (Eastern Europe) origin than in other racial and ethnic groups, but anyone can have them.

[Note: BRCA, which is short for BReast CAncer, is usually pronounced either by saying “brah-kuh” or by saying “B” “R” “C” “A”.]

Source: “Inheriting certain gene changes” (American Cancer Society, 2021)

BRCA Genes and Breast Cancer

Without treatment, a woman who is BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carrier is seven times more likely to develop breast cancer and 30 more times likely to develop ovarian cancer before the age of 70.

A 3-minute video from the CDC.

Understanding BRCA Mutations and Risk

Everyone has the BRCA genes. Their job is to repair errors that occur in your cell’s DNA. If one or both genes you inherited have a mutation, they might let some errors through.

A 4-minute video from the Dr. Susan Love Foundation.

Dispelling myths of BRCA gene mutations

BRCA mutations have been linked to breast, ovarian, pancreatic and prostate cancers, all of which aside from ovarian cancer, can affect men.

A 4-minute video from AstraZeneca.

Black & BRCA is a collaboration between the Basser Center for BRCA and its team of patient advocates, researchers and healthcare professionals to bring tailored resources and support to the Black community. The Basser Center is part of the University of Pennsylvania Health System, a major multi-hospital health system headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“At a time when Black men and women are more likely than the general population to be diagnosed with cancer at later stages when it is less treatable, Black & BRCA seeks to empower individuals to understand their family health history and take action to prevent cancer from one generation to the next.”

Educational Resources

My Experience as a BRCA Mutation Carrier

Erika Stallings is a lawyer, writer, and patient advocate based in New York City. In 2014, she learned that she carried a BRCA2 mutation like her mother.

Despite my risk, I avoided getting tested right away. I was busy living life. Before I knew it, I was 28 years old, about the same age that my mom was first diagnosed.

I knew I needed to get tested. Looking back, I’m a little embarrassed that I pushed it off. But when you’re young, you feel healthy. You don’t expect these huge hurdles to come up, even if you know you’re at risk.

I tried to make an appointment for genetic testing at Memorial Sloan Kettering, but was waitlisted due to a shortage of genetic counselors in the United States. In June 2014, I got an appointment at New York University. I did some volunteer work for a breast cancer organization in New York City, and the executive director helped me get an appointment. If it weren’t for them, I would’ve had to wait another six months.

In July, I got the results. I had inherited the BRCA2 mutation. I knew it.” She underwent a preventative mastectomy later that year.

Source: “My Experience As a BRCA Mutation Carrier”(August 25, 2021)

BRCA gene mutations in men

Men with a mutation in the BRCA2 gene also have an increased risk of breast cancer, with a lifetime risk of about 6 in 100. BRCA1 mutations can cause breast cancer in men, too, but the risk is lower, about 1 in 100. BRCA mutations also increase the risk of prostate and pancreatic cancers in men.

Men with a mutation in the BRCA2 gene also have an increased risk of breast cancer, with a lifetime risk of about 6 in 100. BRCA1 mutations can cause breast cancer in men, too, but the risk is lower, about 1 in 100. BRCA mutations also increase the risk of prostate and pancreatic cancers in men.

Although mutations in these genes most often are found in members of families with many cases of breast and/or ovarian cancer, they have also been found in men with breast cancer who did not have a strong family history.

Mutations in CHEK2, PTEN and PALB2 genes might also be responsible for some breast cancers in men.

Source: Risk Factors for Breast Cancer in Men (American Cancer Society, 2018)

For more information about signs, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in men, see “Breast Cancer in Men” on the American Cancer Society website.

While cancer risks in male BRCA mutation carriers are not as dramatically elevated as those of female BRCA mutation carriers, cancer risk management and early detection are vital.

It is important for both men and women to remember that a family history of breast, ovarian, prostate or pancreatic cancers on their father’s side of the family may indicate a hereditary gene mutation.

Many people mistakenly believe a family history of breast or ovarian cancer only matters on their mother’s side of the family. Men can inherit a BRCA gene mutation from their mother or father and can pass on their BRCA gene mutation to their male and female children.

Medical management for men with BRCA1/2 mutations changes at age 35–40. Ages at which screenings begin are dependent on family history and should be discussed with a physician.

For more information about screening and genetic testing, see “BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Men” on the Basser Center for BRCA website.

Beyoncé's father is a BRCA carrier and cancer survivor

Mathew Knowles, 67, a music industry executive and father of singer Beyoncé, noticed blood spots on the new white T-shirts his wife Gena bought him in 2019. “I said, oh, maybe it’s something to do with these shirts,” he remembered. But when Gena found blood on the sheets on his side of the bed, an alarm bell went off.

Early in his business career, Knowles worked for Xerox selling breast cancer diagnostic imaging equipment to hospitals and health facilities. A breast discharge, he had learned, was one of the signs of male breast cancer.

“So I immediately called my referring physician, said I need to get a mammogram. We got one immediately like the next day and then we got a biopsy.” Diagnosis: breast cancer. A few days later, Knowles had a unilateral mastectomy.

Genetic testing revealed he carried a BRCA2 gene mutation. His family history suddenly made sense. His maternal aunt and her two daughters had died of breast cancer and four of this father’s brothers died from prostate cancer. BRCA mutations increase the risk of both cancers.

Knowles is now cancer-free. Beyoncé and her sister Solange have tested negative for the mutated BRCA2 gene, according to reports in the media.

5 minute video from American Association for Cancer Research

"I had known a long time that the mutation was a possibility"

“I learned in 2007 that my mom carried a BRCA2 mutation after she was diagnosed with breast cancer for a second time. Children of mutation carriers have a fifty percent chance of carrying the mutation as well. By the time I underwent genetic testing in 2014, I had known for a long time that carrying the mutation was a possibility,” says lawyer and cancer activist Erika Stallings.

“When I got my genetic testing results, my oncologist recommended that I have a preventative mastectomy as soon as possible given my family history. I was 29 when I received my test results and my mother had breast cancer for the first time when she was 28 years old.”

“I would advise all Black women to take the time to learn their family health history. If you have a family history of cancer, you likely need to start screenings such as mammograms and MRIs before the age of 40 and you may need to consider genetic testing. I always tell people that the patient/provider relationship is a partnership. If your doctor is unresponsive when you bring up risk for breast cancer, find a provider that will take your concerns seriously.”

Source: Black & BRCA interview with Erika Stallings on the Black Girl Affirmed website

Read more at Erika Stallings’ website.

Disparities in breast cancer genetics?

African American and White Women share same genes that increase the risk of breast cancer

The same genes that increase the risk of breast cancer in U.S. White women also greatly increase breast cancer risk among African American women. Previous studies of women of African ancestry were too small to assess genes other than BRCA1 and BRCA2.

The same genes that increase the risk of breast cancer in U.S. White women also greatly increase breast cancer risk among African American women. Previous studies of women of African ancestry were too small to assess genes other than BRCA1 and BRCA2.

“This means that the multi-gene panels that are currently available to test women diagnosed with breast cancer or women at high risk due to their family history will be useful for African American women,” explains Julie Palmer, ScD, (left) of the Boston University School of Medicine.

Researchers in 2020 sequenced the germline (inherited) DNA from 5,054 African American women with breast cancer and 4,993 age-matched African American women without cancer for mutations in 23 genes linked to a predisposition for cancer. They then estimated the risks of developing breast cancer associated with having a mutation in any of the genes.

- Source: “African American and White Women Share Genes that Increase Breast Cancer Risk” on the Boston University School of Medicine website

- See the full text of the scientific paper “Contribution of Germline Predisposition Gene Mutations to Breast Cancer Risk in African American Women” by Julie R Palmer et al.

Rates of genetic mutations similar between Black and White women diagnosed with breast cancer

In a 2021 study of 3,946 Black women diagnosed with breast cancer and 25,287 White women also diagnosed with the disease, the rates of genetic mutations in genes linked to breast cancer were similar. Among the Black women, 5.65% had a mutation in one of the 12 genes, compared with 5.06% of the White women, a difference that is not statistically different.

In a 2021 study of 3,946 Black women diagnosed with breast cancer and 25,287 White women also diagnosed with the disease, the rates of genetic mutations in genes linked to breast cancer were similar. Among the Black women, 5.65% had a mutation in one of the 12 genes, compared with 5.06% of the White women, a difference that is not statistically different.

The researchers, led by Susan Domchek, MD, (right) of the University of Pennsylvania, concluded that all efforts should be made to ensure equal access to genetic testing to minimize disparities in care and outcomes in women diagnosed with breast cancer.

- Source: “Do Black Women Diagnosed With Breast Cancer Have Higher Rates of Genetic Mutations Than White Women?” by Jamie DePolo on the breastcancer.org website

- See the full text of the scientific paper “Comparison of the Prevalence of Pathogenic Variants in Cancer Susceptibility Genes in Black Women and Non-Hispanic White Women With Breast Cancer in the United States” by Susan M. Domchek et al.

Recent news about disparities in genetic mutations

Breast cancer genetic testing

Genetic testing to learn about breast cancer risk

Genetic testing gives people the chance to learn if their breast cancer or family history of breast cancer is due to an inherited gene mutation.

Genetic testing gives people the chance to learn if their breast cancer or family history of breast cancer is due to an inherited gene mutation.

In the United States, 5 to 10 percent of breast cancers are related to a known inherited gene mutation. About half are related to a BRCA1 or BRCA2 inherited gene mutation.

Other inherited genes are less common and most don’t increase the risk of breast cancer as much as BRCA gene mutations do, but they can increase the risk of other cancers. Data on these mutations and their related cancer risks are still emerging and will likely change over time.

More at: Genetic Testing to Learn About Breast Cancer Risk (Susan G. Komen)

Genetic testing to guide breast cancer treatment

Genetic testing may be recommended after a diagnosis of breast cancer to look for gene mutations that have been inherited. Some breast cancer treatments are given only to people who have certain inherited gene mutations.

Knowing about inherited mutations and the risk of cancer can also be important information for other family members.

Testing for gene mutations in the tumor itself may also be done. For some people, this can help guide treatment.

More at: Genetic Testing After a Breast Cancer Diagnosis (Susan G. Komen)

Groups at Higher Risk for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer

Most hereditary breast cancers are caused by abnormal BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. However, even if a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation does not run in the family, a strong family health history of breast cancer makes it more likely that a person will get breast cancer, possibly due to mutations in other genes. Mutations in several other genes also have been linked to breast and ovarian cancers.

The first step in assessing your risk is learning your family history and sharing this information with your health care provider to learn if genetic counseling and testing are right for you.

See more at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: “Groups at Higher Risk for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer”

Testing for the BRCA genes isn’t routinely performed in people with an average risk of breast cancer. It’s usually offered only to those who are likely, based on a personal or family history of cancer, to have an inherited mutation. The identification of a mutation may affect the treatment recommendations, make a patient eligible for certain clinical trials, and alert other members of a family that they may have also inherited the mutated gene.

If your genetic testing was performed prior to 2014, updated testing should be considered. Earlier testing most likely would not have included looking for PALB2 or other potentially relevant genes and may not have included testing for large genomic rearrangements in BRCA1 or BRCA2.

Sources:

One of key reasons to do BRCA testing: to find out if you're at greater risk for ovarian cancer, too

“If you for example have a family history of breast cancer or a personal history of breast cancer, you might not be thinking that you’re at risk for ovarian cancer,” says Susan Domchek, MD, Executive Director, Basser Center for BRCA at the University of Pennsylvania. “But that risk is as high as 45 percent.”

“Ovarian cancer, unlike breast cancer, has no effective screening. It unfortunately usually presents late and most people die of that cancer.

So, it’s a cancer we very much want to prevent. One of the key reasons to do genetic testing is to figure out whether you’re at risk for ovarian cancer and to act on that information.”

A 3-minute video from Penn Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Why you shouldn’t rely on direct-to-consumer genetic testing to determine your BRCA status

More than 1,000 variants of the BRCA genes are known to increase the risk of cancer. 23andMe genetic testing , the only FDA-authorized, Direct-To-Consumer BRCA Test, detects only the three variants most common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. These variants are rarely found in people of other ethnicities, the company points out.

“It’s important to talk with your doctor or a genetic counselor about your family history to determine whether additional and/or comprehensive genetic testing may be appropriate,” 23andMe advises.

Who should speak to an expert about genetic testing

Experts recommend that people diagnosed with breast cancer who have any of the following should speak to an expert about genetic testing:

- Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

- diagnosed with breast cancer more than once

- breast cancer diagnosed at age 45 or younger

- male breast cancer

- advanced or metastatic breast cancer

- early stage breast cancer at high risk for recurrence

- a close blood relative who tested positive for an inherited mutation in a gene linked to cancer risk

- close blood male relative diagnosed with breast cancer

- Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry

- lobular carcinoma and a personal or family history of diffuse gastric cancer

For more reasons to seek genetic counseling, see “Genetic testing for people who have been diagnosed with breast cancer” (FORCE: Facing Hereditary Cancer Empowered)

Genetic Counseling

Get Genetic Counseling Before Testing

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says it’s important to get genetic counseling before genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in order to determine whether you and your family are likely enough to have a mutation that it is worth getting tested. Usually, genetic testing is recommended if you have:

- A strong family health history of breast and ovarian cancer

- A moderate family health history of breast and ovarian cancer and are of Ashkenazi Jewish or Eastern European ancestry

- A personal history of breast cancer and meet certain criteria (related to age of diagnosis, type of cancer, presence of certain other cancers or cancer in both breasts, ancestry, and family health history)

- A personal history of ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer

- A known BRCA1, BRCA2, or other inherited mutation in your family

Carletta (above) tested negative for BRCA mutations after being diagnosed with breast cancer.

Source: “Genetic Testing for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer” (CDC)

To find genetic counseling services:

- Find a genetic counselor using the National Society of Genetic Counselors directory.

- Find a genetics clinice using the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Genetics Clinics Database.

Source: “Genetic Testing for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer” (CDC)

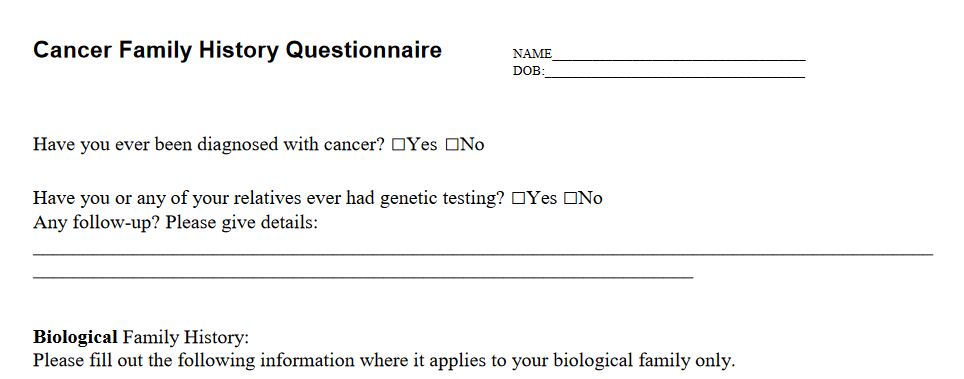

Recording your family history

Cancer Family History Questionnaire from cancer.net

My Family Health Portrait: an online tool from the Surgeon General

Disparities in breast cancer genetic testing?

Racial Disparities Persist in Genetic Testing

Carlette Burton knew she had a family history of cancer, but she never looked into her genetic risk for BRCA-related cancer until she found a concerning lump in her breast during a self check. After her diagnosis, she had genetic testing done and found out that she has a BRCA mutation.

Burton’s mother also had been diagnosed with breast cancer in her 30s. Her grandmother had had breast cancer, too. She is one of five sisters, “but I don’t ever recall a doctor saying we should get tested.”

Read more at “Racial disparities still persist in genetic testing for BRCA-related breast cancer” by Tracey Romero on the Philly Voice website (April 6, 2021)

Black women less likely to undergo genetic counseling and testing

About five percent of both Black and white women have a genetic mutation that increases their risk of breast cancer, according to a new study of nearly 30,000 patients.

However, compared to White women, Black women are much less likely to undergo genetic counseling and testing, largely due to differences in physician recommendations or access to care.

“Our efforts should focus on ensuring equal access to testing to minimize disparities in care and outcomes,” said researcher Susan Domchek of Penn Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (June 11, 2021)

Read more at “Black and White Women Have Same Mutations Linked to Breast Cancer Risk” on the Penn Medicine website (June 11 , 2021)

Testing for the BRCA genes isn’t routinely performed in people with an average risk of breast cancer. It’s usually offered only to those who are likely, based on a personal or family history of cancer, to have an inherited mutation. The identification of a mutation may affect the treatment recommendations, make a patient eligible for certain clinical trials, and alert other members of a family that they may have also inherited the mutated gene.

Genetic testing performed prior to 2014 most likely would not have had PALB2 or other potentially relevant genes included and may not have included testing for large genomic rearrangements in BRCA1 or BRCA2, so updated testing should be considered.